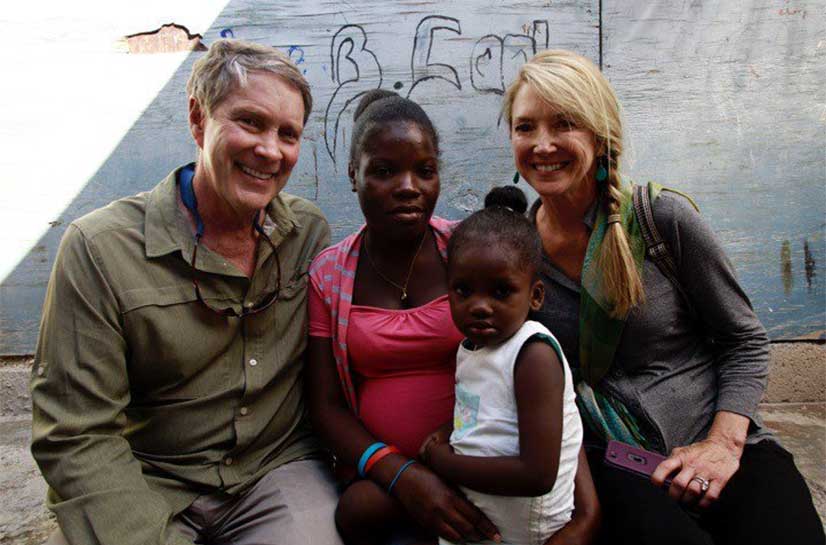

As I hope you’ve heard, there is an outbreak of the Ebola virus in Western Africa right now, particularly in Liberia. Two American aid workers, Dr. Kent Brantly with Samaritan’s Purse and Nancy Writebol, a volunteer working with the faith group Service in Mission, were recently infected.

I’ve been discussing the situation with the Centers for Disease Control, and I wanted to write a little bit about the transmission and natural history of the virus.

Ebola is a type of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF). Four families of viruses cause VHFs, and Ebola is from the family Filoviredae. Dengue fever, Yellow fever, Crimean Congo fever, Hantavirus and Lassa fever are other types of VHFs you may have heard of.

Humans are not a natural vector for the Ebola virus, so outbreaks occur after a human comes in contact with an infected animal such as a monkey, pigs or especially bats. Human-to-human spread then occurs through contact with bodily fluids such as urine, secretions, blood, stool or contaminated medical equipment.

Ebola is not technically contracted by respiratory contact with an infected individual, but aresolization of secretions—for example, a coughing patient—can cause spread of the virus. Therefore, barrier precautions like gloves and gowns as well as airborne precautions like masks and goggles (to prevent absorption through the cornea of respiratory droplets) are necessary to prevent transmission. For healthcare workers, infection is almost exclusively the result of a tear or other weakness in their protective barriers.

VHF viruses are dangerous because they are highly contagious, have a high rate of infectivity with low doses of exposure and high rates of complications and death. Therefore, it is important to recognize the signs and symptoms to quickly isolate potentially infected individuals. First, the individual’s travel history is important if not already in an endemic area. Second the timing is helpful to raise suspicion. The incubation period is a few days to weeks. The illness begins with fever and muscle soreness, low blood pressure, red eyes and a rash (specifically, petechial hemorrhages). The constellation of these symptoms with potential exposure is enough to warrant immediate quarantine.

The virus then attacks blood vessels all over the body and increases vessel permeability resulting in fluid loss and bleeding. The fluid and blood loss causes shock and disorders of the clotting system resulting in hemorrhage from mucous membranes as well as in internal organs such as the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. While there are experimental drugs under research and being used in Liberia today, the only known available treatment at this time is supportive care. Supportive care includes fluids, blood products, blood pressure and respiratory support and possibly comfort measures.

The key to survival of Ebola is immediate and sufficient isolation of infected individuals and treatment with aggressive supportive care in an intensive care setting. Once patients have stabilized they are no longer infectious and can be taken out of quarantine. The virus is so rapidly fatal that naturally occurring outbreaks can be contained if patients are quickly isolated and effective barrier and airborne precautions implemented.

There are some experimental drugs for Ebola, but none have completed clinical trials and some have only been tested in lab animals. Many are arguing that the most advanced of these treatments be made available to the sick, even though they haven’t been fully tested yet. One such serum was administered to Ms. Writebol. Dr. Brantly has had a blood transfusion from a boy who survived the virus, in hopes that some antibodies to the virus may be transferred.

Much of the outbreak problem in West Africa can be attributed to lack of knowledge about the virus to recognize and immediately quarantine the sick, as well as the cramped facilities where the healthcare workers were operating. West Africa has never seen Ebola before, and most healthcare facilities are not properly equipped to handling the kind of quarantine needed.

The Centers for Disease Control is currently working to send in personnel and supply support to help contain the virus. Dr. Friedan, the director of the CDC, has little fear of spread to the U.S. due to quarantine posts at all points of entry. He also predicts it may take up to six months to completely contain the virus in Liberia, but he’s confident of eventual success.

Join me in praying for all of the infected individuals and the healthcare workers on the ground and abroad that are making efforts to help contain the outbreak.

What’s next?