The following is text of remarks delivered on the Senate floor.

Jan. 30, 2003 – Senate Floor Remarks

Mr. President, for a few moments before closing tonight–and we have had a very productive day and we will make the more formal announcements in about 15 minutes or so–I take a few moments addressing an issue that means a lot to me, personally, and to take a moment to reflect upon an announcement that the President made at the State of the Union two nights ago.

It has to do with a little virus, called HIV/AIDS virus, and the devastation it has wrought on individuals, most importantly, but also communities and villages and counties and States and countries and continents and, indeed, the whole world.

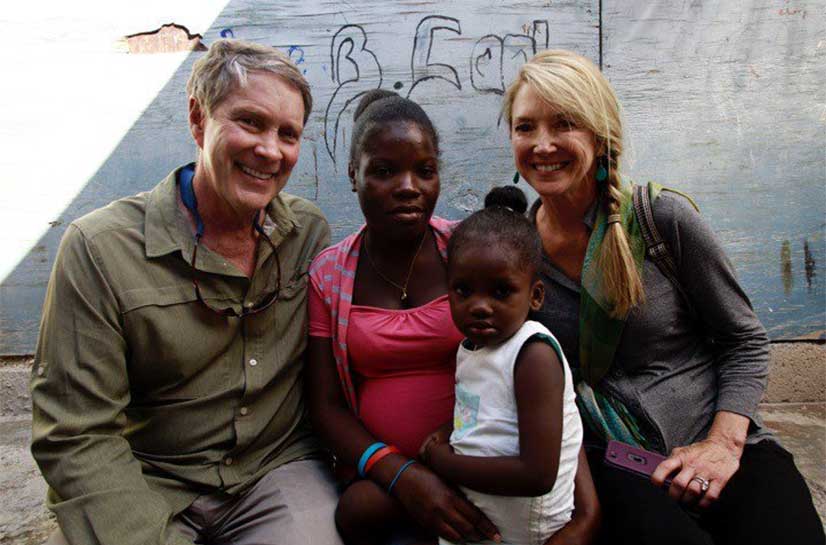

Once a year I have a wonderful opportunity to travel to Africa as part of a medical mission team. I travel not as a Senator, but I have the opportunity to travel as a physician. Last January, on one of these medical mission trips, I treated patients in villages and in clinics and a number of countries in Africa, including the Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya. Many of the patients I dealt with were infected with HIV/AIDS virus. This little tiny virus, a microorganism, causes this disease we all know as AIDS.

I think back to a number of patients. In Arusha, in the slums, conditions are crowded, but as you walk through these very crowded slums, the people there are very proud. While there, I visited with a young woman by the name of Tabu. She lived in a small–by small I mean one room, probably 8 feet by 8 feet–stick-framed mud hut. I remember walking in there, as my eyes adjusted, and seeing a very beautiful woman, 28 years old, sitting on the edge of the bed–a human smile. And on the walls behind her, to keep moisture out, were newspapers plastered on the walls. Again, things neat and clean, but a very small hut which was her home–a woman with a broad smile who was obviously sick, and very sick, meaning she would die in the next week to 2 weeks.

She lived in this, her home, with her 11-year-old daughter, Adija, whom I also met, although her other children did not live with them in that hut because Tabu was so ill and so sick that she simply couldn’t physically manage having the other children there. As she explained her story to me–again, I was the physician from America who came to be with her–her story was one she was a little bit embarrassed about because she literally had to send her children away because of her disability–her physical disability, due to this little tiny virus–to send them away to live with her mother who could take care of her children.

I mentioned her smile. As my eyes adjusted, I saw that she was indeed wasted, thin and sick, but her eyes and her smile were full of hope. That smile in many ways hid the pain of that illness, the pain of having to send her children away. The next day, she left her hut and she was going to go live with her mother for the last few days of her life, to die in her childhood home.

Tabu told me she was one of four sisters, all of whom had HIV/AIDS. All had been infected with the virus. Musuli, a sister 20 years old, who lived with her mom; Zbidanya, 15 years of age; and an older sister, Omeut, who had already died.

Tabu died the next week. But she didn’t have to. If we do our job and if we follow the bold leadership as spelled out by the President of the United States, we can cure this disease, a disease that is destroying nations–indeed, destroying a continent, and mercilessly and relentlessly spreading throughout the world–Russia and China and the Caribbean.

That face of Tabu, there in Arusha, in that home, is indeed the face of AIDS in Africa and in nations around the world.

The little tiny virus is not all that different from the viruses I am quite accustomed to treating in the population I treated before coming to the Senate, that can tear apart individuals, but this virus is different in that it is smarter. It is more cagey than other viruses. But it is still just a little microorganism that is wiping out these continents, a little tiny virus. It is ravaging families. It is causing mass destruction, this little tiny virus. It is ravaging societies. It is ravaging economies. It is ravaging countries. And, indeed, it is ravaging whole continents. To my mind, there is no greater challenge, morally or physically, facing the global health community today than this global health crisis.

The other interesting thing about it is, it is new. Usually if you have something this devastating, you think it has a long history and has grown over the years and over the centuries. But it is new. When I was in medical school, we had never heard of an HIV virus; we had never heard of the disease called AIDS. I am not that old; 1981 was the first time in this country we were smart enough to figure out that there is this little HIV virus that causes AIDS–1981. That is 22 years ago.

But since that pandemic–epidemic means a disease spreading in one part of the world. A pandemic is just that, it is spreading all over the world. That is where the “pan” in pandemic comes from. Since 1981, more than 60 million people have been infected with this little virus that wasn’t around 23 years ago. That is basically the population of the great State of New York times 3. Twenty-three million people have died from this little tiny virus. And we are losing the battle. We are fighting it, but it is a battle we are losing as we go forward.

For every one person who has died since I was in medical school, say, since 1981 when we first discovered it in this country, for every one person who has died in the last 20 years, in the best of all worlds, if we do everything perfectly, we do everything right, for every one person who died in the last 20 years, two people are going to die in the next 20. That is in the best of all worlds.

Why is that? Because there is no cure for this virus. People hear me talk on this floor a lot about vaccines, saying we need to protect the infrastructure and fight bioterrorism with these vaccines. We do not have a vaccine for this little tiny virus. So we have no cure. We have no vaccine to prevent it. As I said earlier, this little virus is smart. Whenever we have a therapy that works pretty well, the little virus changes itself–probably 1,000 times faster than other viruses–so it will defy that treatment. Every time we get a treatment, it changes itself. It is a cagey virus.

The virus causes AIDS. AIDS is the disease, the manifestation. Tabu, being wasted and thin–the virus itself is what causes it. What do we know about the disease itself? Whom does it hit? Put aside perceptions, the stigma of AIDS. Put them aside. Let me tell you about the virus. The virus hits young people. Eight hundred thousand children were infected in 2002. Young people account for 60 percent of the new HIV infections each year. Worldwide, 13 million people have been orphaned by AIDS. Most of them are, indeed, in Africa. When you are orphaned by AIDS; you are left without mentors; you are left without parents; you are left without a supportive structure; you are left without the support we have in other, more advantaged, countries.

As I go to Africa on these mission trips–again, I go down as a physician–you have the opportunity to go walking through villages. Nothing really can prepare you for walking through a village and looking at the people in the homes. You see very old people–not very old, but old for the society there–people in their seventies, sixties, fifties. Then you see just little kids running around. What you do not see are people 20 years of age, to 35, to 40 years of age. It is almost like this whole segment of the population has been wiped out–old people and young people, but nobody in their productive years.

That is what you see if you go to Nairobi and you walk through the Kibera slums, which go on, it seems, forever. When you walk through the slums, you don’t see people in their most productive years.

Entire generations are being wiped out, and kids are growing up in the streets with no parents and no mentors. And that all translates down into no hope.

What is fascinating is that we have the power to bring them hope. That is why I get excited when the President thinks big. And he articulated that in the State of the Union speech. It is thinking big because we have the power to bring them hope. We must ask ourselves, How can we, since we have that power, not use that power? Most people do not realize the disease of AIDS caused by the virus is today a disease of predominantly women. It is just not part of what we historically have pictured what this disease is all about. More than half of all the people now infected with AIDS are women. With AIDS on a rampage through the villages of sub-Saharan Africa, life expectancy in Africa is now 47 years of age. I wouldn’t be alive at 47 years of age. What is interesting is, what increment is due to this little, tiny virus? If the HIV virus had never appeared over the last 20 years, instead of living 47 years you would live 62 years–just because of this little virus.

If you are born in Botswana, you are not going to live to 47 years, or 45, or 43, or 42, or 41. You may live to the age of 38. Average life expectancy, if you are born in Botswana today, is 38 years of age because of this single little virus wiping out people, destroying people, killing people in their most productive years.

In 2005, in Zimbabwe, 20 percent of its workforce will be wiped out due to AIDS. Death is tragic enough. Taking this productive segment of society, very quickly you have to ask yourself, with that productive segment as parents and with the infrastructure of civil society disappearing, what happens to the children who are left behind? Who will feed the children? Who will mentor those children?

Law enforcement is being wiped out, and teachers are being wiped out. Kenya has reported in recent years as many as 75 percent of the deaths in law enforcement, in its police force, are AIDS-related. In civil society the potential for disruption is obvious.

If you look at what this little tiny virus incrementally does to the economy of these countries, we see we can give unlimited aid and money, but unless we defeat this little virus, the economies are not going to grow; they are going to diminish. If you look at those countries where the prevalent rates are about 20 percent or so–which is, in medical terms, significant penetration, but not unusual for Africa–the economy doesn’t grow but drops 2.6 percent a year because of the HIV/AIDS virus. Why? Because you wipe out the most productive people in that society. We see poor countries growing poorer because of the virus, not just financially, which is how we measure gross domestic product, but spiritually. The hopelessness, the helplessness that comes from this little virus, all of a sudden becomes the norm.

What is the role of the United States of America, especially in light of the President’s pronouncement the other night? Historically we have much to be proud of. I think we need to add that, because we read about people from other countries and people associated with the United States who have never stepped to the plate. I want to disabuse my colleagues and people who are listening. The United States has already done much to combat global HIV/AIDS in terms of research, and in terms of financial investment, both unilaterally and bilaterally. You hear about the Global Fund on AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria–an important fund, a new fund, that hasn’t yet been proven. But it becomes sort of the marker in many people’s minds of what we are contributing. In truth, it is one part of a huge battle–a lot of resources that were actually invested in fighting AIDS, but in terms of that Global Fund on AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States was the first donor under President Bush. In a second round of financing, we once again were the first donor to that fund. Before the President’s announcement, we were that global fund’s largest donor. We placed $500 million, more than any other nation. That is a quarter of all the pledges. The next closest country hasn’t even matched half of our commitment.

I say that because I am offended when people say the United States simply has not stepped to the plate. Just as impressive is the speed with which we have addressed this issue historically. We ramped up funding dramatically in both direct aid, bilateral aid, and global fund money.

Total funding in 1999 was $154 million. Remember, the President two nights ago was talking about billions of dollars. Just 4 years ago we spent totally $159 million. In the last 4 years, there has been an eightfold increase, up to about $1.2 billion. Indeed, the United States is today leading–even before the President’s announcement–the global fight against HIV/AIDS. I think we can be proud of that. But–and is where the President’s announcement came–we can do more. I believe in support of what the President has said from a moral standpoint, we can and should and will do more.

I mentioned we are losing the battle. Every 10 seconds somebody dies of the infection. But in that same 10 seconds there are two new infections. Remember that we have no cure. That is right now. That shows there is so much to be done. Each death and each new infection is one more tragic battle lost in the war against this killer virus.

I think, I know, that we have a moral obligation and a human requirement to provide more resources to fully enter the big war to win the battle one person at a time. Those resources must be managed and monitored so they get to those people who we intend to help. The process must be transparent. I know that the President, because he has told me personally and in meetings many times, wants to invest that money making sure we get results; that the money is used wisely with focus, that it is used transparently, and that we measure the results we set out to achieve.

I think also we in this body need to summon the commitment of all Americans to be soldiers in this war in whatever way they possibly can. I say that only because as elected officials, although we know it is the right thing to do and morally the most powerful thing to do, some constituents around the country ask, Why in the world are you investing in a disease that, yes, affects the world but is predominantly a continent so far away?

One of the reasons I am carrying on this discussion tonight is because I think each of us has an obligation–has an opportunity but also an obligation–to help educate not just our colleagues and people in Congress but people all across America. We need to do that every day in speeches–every time I go back to Tennessee or my colleagues go back to Nevada or South Dakota or Georgia or California. We have made a lot of progress in the last couple of years. With the President’s announcement in the State of the Union Address, I believe we are on the cusp of a truly historic leaf that I believe can turn the tide of this devastating disease, if we will start saving lives and also instilling hope.

Over the past 2 years, Senator Kerry and I, with a bipartisan group of Senators, have constructed and put together what I believe is a significant bill that addresses this little, tiny virus–this cagey virus that is causing this mass destruction–and which addresses the moral challenge this virus represents. The legislation will be discussed in the Foreign Relations Committee next week, led by the Senator from Indiana, chairman of that committee, Senator Lugar. I hope this bill becomes the legislative counterpart to President Bush’s bold initiative.

The President has pledged more resources, significantly more resources, a tripling in funding. He has proposed an emergency plan, and he has used–this may be the most significant thing–the bully pulpit to rally a great Nation to this noble cause. He sets the gold standard for humanitarian efforts for the United States but also for the world. I know he has personally committed to achieving results. His proposal, once our bill is acted upon, will prevent 7 million of these new infections, will provide the antiretroviral drugs for 2 million HIV-infected people, will care for 10 million HIV-infected individuals and AIDS orphans, and will provide $15 billion–$15 billion–in funding over the next 5 years.

I should also add that, as a government, we cannot do it alone. Even single leaders cannot do it alone. Even what this body does cannot do it alone. It is truly remarkable, as I have been addressing this particular issue over the last 8 years, to see this new intersection, this new coalition of partners that heretofore just has not existed. It has not existed. By that I am talking about the pharmaceutical companies. At the end of the day, it is going to be the research of the pharmaceutical companies–in developing vaccines, in figuring out why this virus changes–that will give much of the answer. The pharmaceutical companies, the faith-based community–the churches, the spiritual community–the academies, and the universities all across this great Nation are coming together at this intersection, along with Government and along with, I should add, the private sector and foundations.

I mention the foundations because we just saw an announcement last week by Bill Gates. It is significant, with big numbers, huge numbers going to global health. We have seen nothing like this in the history of the world. It comes from a foundation that, in truth, moves a lot faster than Government can move. We have been working on the HIV/AIDS issue for years and years and years. Bill Gates basically said: Listen, I see the problem. I am going to go out and do my best to lick the problem. Indeed, he announced this past week a remarkable $200 million grant to establish what is called the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative. This is going to be a major new effort and a partnership with our NIH, our National Institutes of Health, which will accelerate research on the most difficult scientific barriers in global health.

Today, only 10 percent of medical research in this country–only 10 percent–is devoted to the diseases which account for 90 percent of the health burden in the world. Mr. Gates said: It doesn’t make sense. For 90 percent of the health burden in the world, we are only spending 10 percent of our research dollars. Let’s do something about it. He is in a position to do just that. Through his foundation, he will change just that.

The Gates initiative will provide grants to support the collaborative efforts of the most creative and innovative scientists and researchers in the world. The initiative will draw attention to these urgent global health research needs. And it will stimulate where I think the real answer is going to be; that is, the public-private partnerships–the partnerships with the academies, with the churches, with the pharmaceutical companies, with the leadership, yes, of the United States and other of the wealthier countries, but also the leadership of the disadvantaged countries, the countries that are being subjected to the ravages of HIV/AIDS.

I would not have said this 4 years ago, but we will defeat this little virus. When I close my eyes, that is what I see: this little virus–and all the death and destruction–but this little tiny virus, in part because I am a doctor. When I think of disease, I always look at the cause of it. But it is that little virus. We will defeat it. Let me repeat that: We will. It will be with the leadership of the United States of America. And by “leadership,” I am talking about this body, working with the President, working with the House of Representatives, working with the public-private partnerships. With that leadership, we will defeat this virus.

But the question is–and the reason timing is important–how many children and women and men are going to die before we defeat the virus? I already told you, in the best of all worlds, for every one person who died in the last 20 years, two are going to die in the next 20. Even if we discovered a vaccine right now, that is going to happen, because the vaccine is for prevention.

The real question is, Will 60 million or 80 million or 100 million people die? Or, again, under the leadership of the President of the United States, and with the legislation that we can generate in this body, instead of it being 100 million, can it be 20 million or 40 million or 45 million or 50 million? Or will it grow from 100 million to 200 million or 300 million?

That is the urgency. That is why we need an emergency response. And that is why, as a physician, as someone who, with my own hands, has had the opportunity to work with hundreds of HIV/AIDS patients in this country and in many countries in Africa, it means so much to me. I have seen that so directly.

The answer is in our hands. Literally, it is in our hands. We are capable today of slowing this pandemic. It is going to increase in the near future. There is nothing we can do about that. But we can slow the trajectory. Indeed, in countries such as Uganda it has already flattened and decreased, so we know there are things we can do now to reverse this trajectory. But we have to choose to fight first. We need to make that commitment the President made 2 nights ago and fight it with our will, fight it with resources, fight it with energy and as much spirit as we can muster.

I will close because I know it is late, and we have worked again aggressively over the course of the day and have made real progress, but I will close by simply saying, the President, I know, is committed in both word and deed. I think it is now time for our body, this legislative body, to come together to work for this legislation and help lead a great people and a great nation to overcome one of the greatest moral and public health challenges the world will face in the 21st century.