(Reuters, November 5, 2013 )

By Bill Frist

In an HIV clinic in Africa, a man born deaf holds a single sheet of paper with a plus sign. He looks for help, but no one at the clinic speaks sign language. In fact, the staff doesn’t seem interested in helping him at all.

He returns to his plus sign. These are his test results. They dictate he should start antiretroviral drugs immediately and should also make changes in his sexual habits. But he doesn’t know this. He leaves the clinic concluding that the plus sign must mean he’s okay, that everything is just fine.

This scenario seems shocking. Yet it continues to play out around the world. The Senate will tackle this issue at the November 5th hearings on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) — the Disabilities Treaty.

There are nearly 1 billion people worldwide living with a disability. For the sake of those individuals, the United States joined 158 other countries in signing the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2009. The Disabilities Treaty was drafted to promote and protect the human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons with disabilities — modeled on our own Americans with Disabilities Act, but on a global scale.

Yet the Senate failed to ratify the United Nations treaty last December. As is often the case, a bit of politics and a bit of misinformation ruled the day.

First, the timing was bad. The vote was called in a lame duck session and many senators said this was an inappropriate time to ratify a U.N. treaty, signing a letter to that effect. But this was not the entire story.

Two larger political issues emerged. Republicans exhibited some squeamishness around the term “sexual and reproductive health” in the treaty. While the term is undefined, there were rumblings that it could create a global right to abortion.

The second issue was an impressive fear campaign launched by Michael Farris of the Home School Legal Defense Association to convince parents that the U.N. treaty would limit their ability to educate their disabled children at home.

The relevant provisions in the treaty regarding sexual and reproductive health demand nondiscrimination for persons with disabilities.

In many parts of the world, people with disabilities, regardless of age, are believed to be sexually immature or inactive. The assumption can make them targets for rape and other sexual crimes while, at the same time, gynecologic and obstetrical care are withheld and considered inappropriate and unnecessary. In other cases, they are forcibly sterilized or forced to have abortions, simply because they have a disability.

The treaty’s “sexual and reproductive health” language is a necessary provision to protect these people. It does not define services — a ratifying country’s existing law provides the definition. The agreement simply demands that those with disabilities not be denied any treatments based on their disability.

It does not create any new services not previously available or legally sanctioned in an adopting country.

For the home schooling debate, the story is more complicated. The Americans with Disabilities Act — on which the international agreement is modeled — has a strong history of Republican support.

Consider, the disabilities act was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush — passed with a 76 to 8 vote in the Senate. President George W. Bush negotiated the CRPD treaty in 2006. Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) and former Senate Majority Leader Robert Dole, who had each suffered serious war injuries, were significant supporters. Senator Jerry Moran, a Republican from Dole’s home state of Kansas, also initially supported it.

The tide turned, however, at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on July 12, 2012. Farris, president of the home-schooling organization, claimed in testimony that the U.N. treaty was “dangerous” for parents who teach disabled children at home. He asserted that it will create a legal basis for the United Nations to infringe on the fundamental parental rights of parents of disabled children.

In a radio interview after the hearing, Farris stated “[t]he definition of disability is not defined in the treaty and so, my kid wears glasses, now they’re disabled; now the U.N. gets control over them.”

It sounded terrifying.

Then-Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry dismissed Farris’s argument out of hand. But the home-schooling organization has an impressive grassroots machinery.

Within a few weeks, Farris’s argument spread. Senator James Inhofe (R- Okla.) and then Senator Jim DeMint (R-S.C.) wrote an op-ed article for the Washington Times stating the treaty would infringe on U.S. sovereignty. Farris’s group began a phone campaign to all senators who might be potential nay votes — specifically targeting the Kansas senators. Senator Rick Santorum, a parent of a disabled child, adopted Farris’s argument as well.

The probable nail in the coffin was when Moran changed his position to align with the HSLDA.

But despite the successful political maneuvering of Farris’s home-schooling organization and its capture of many Tea Party senators, careful reading of the law reveals their arguments were a misinterpretation.

U.S. ratification of the treaty does make the agreement a U.S. law, along with the Senate’s reservations, understandings and declarations (RUDs). However, these RUDs make it clear that current U.S. law — the Americans with Disabilities Act — meets any U.S. obligation under the treaty. In fact, the ADA and related disability laws far exceed the standards set out in the U.N. treaty. Ratifying the agreement will not affect current enforcement of the ADA or create additional causes of action under the treaty. The Americans with Disabilities Act would remain the controlling U.S. law.

The U.N. experts committee cannot make international law and therefore cannot create new international obligations. The committee can make suggestions for improvement during a review process. But these recommendations are just that — recommendations. The United Nations will have no ability to swoop in and poach parental control over the education of children with disabilities in the United States.

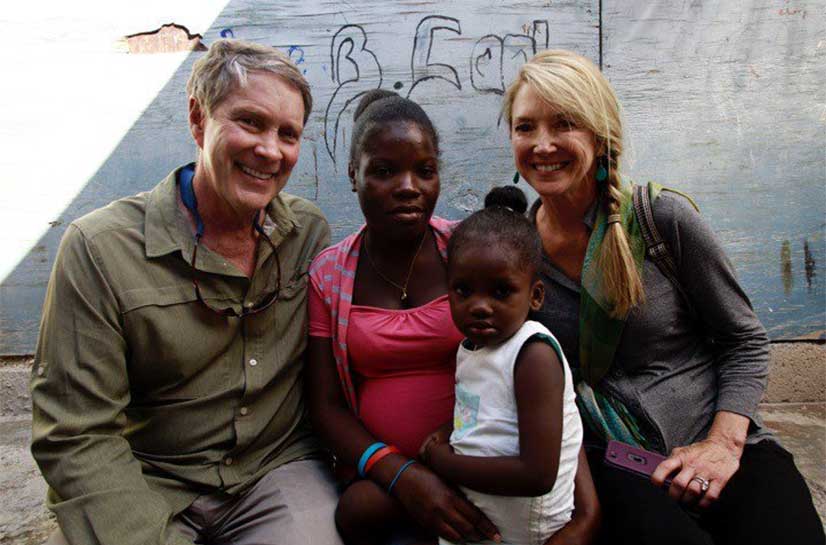

Some still argue that the United States has no need to ratify the U.N. treaty. The Americans with Disabilities Act, they insist, already protects the rights of those with disabilities at home. But as a global leader, we must stand with those struggling for the rights that we hold dear.

These are complicated issues revolving around potentially esoteric points of international law. Given this complexity, many senators felt the previous hearings were rushed and that they did not have enough details to make an informed decision. The set of hearings scheduled for November 5 and 12 will be different. Both witness lists have a deep bench of experts — legal, administrative and activist alike. Now is the time to really unpack what this U.N. treaty would mean for Americans and the world.

Voting no to this treaty without a specific and compelling reason is saying that we do not think the global community deserves an ADA of their own.

U.S. leadership matters. We should be at the table. It is not just Americans who deserve healthcare and protection from discrimination. It is everyone.

The article was originally featured on Reuters: http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2013/11/05/why-the-u-s-must-lead-on-disabilities-treaty/