(Morning Consult, June 23, 2014)

One week ago I had dinner in an open air restaurant overlooking Kigali, Rwanda. It was a beautiful night, and the almost-full moon illuminated Kigali and the land of a thousand hills.

As we were leaving, one of our hosts approached me. A formal and reserved woman, she quietly told me that at the end of her medical school education—about 1999—she almost walked away from the career she’d been building. All of her patients were dying of AIDS; the virus seemed unstoppable. There was nothing she could do to help them. There was no hope.

In despair, she told her Canadian advisor that she was ready to quit medicine. He encouraged her to keep working. “There are therapies to treat this virus in the world. They are young, they are very expensive, but there is reason for hope and optimism,” he told her. “These patients who have led you to despair have a treatment. And someday, if we all work hard, that treatment will be here.”

She had tears in her eyes when she looked up.

“And then,” she said, “you came.”

The “you” was the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief—PEPFAR. PEPFAR initially committed $15 billion starting in 2003 to fight the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. Rwanda was one of the original focus countries.

The United States and PEPFAR turned around a country that had been destroyed, indeed a continent that was being destroyed, by your generosity and your commitment, she said. Drugs that were out of reach, all of the sudden were being distributed to patients.

PEPFAR changed this woman’s life personally too. She stayed in medicine. She became active in public health issues. Today Anita Asiimwe, MD, MPH, is the Minister of State in Charge of Public Health and Primary Care.

I wiped away tears at the earnestness with which Dr. Asiimwe spoke. I looked at Dr. Paul Farmer, who led last week’s Rwanda trip with me, and he was emotional too.

I’ve long believed that health and medicine are the most powerful currency for peace and healing. Public policy matters. The United States is generous and it really affects people’s lives, both patients and providers.

Dr. Asiimwe’s story set the stage for a humbling week.

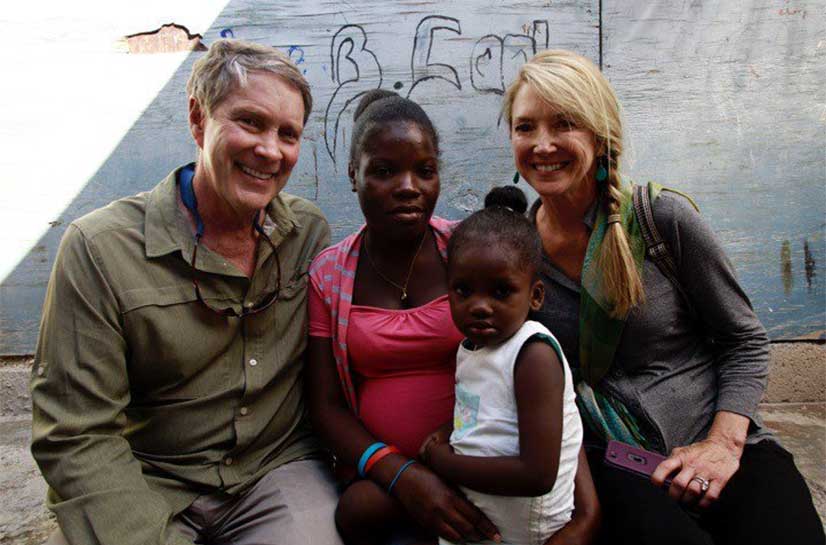

Dr. Paul Farmer, representing Partners in Health (PIH) and Harvard Medical School, and I, representing Hope Through Healing Hands, led a small coalition to learn more about health care in Rwanda and the progress being made there in the past 20 years.

In 1994, twenty percent of the Rwandan population—about a million people—was murdered in a genocide against the Tutsis over a 100 day period. I have studied the origin of the genocide, visited the memorials, talked with the survivors, read the explanatory books and made multiple journeys to Rwanda —but it is still hard for me to fathom. We in the US stood idly by when this happened.

The genocide was rooted in a deep-seated post-colonial divide coupled with eugenic constructs of race grounded in the previous century. All social order was destroyed. HIV infection rates skyrocketed. Child survival plummeted. And health care delivery capacity was nonexistent.

But the people of this country came together and began to rebuild. Formalized programs of reconciliation were embedded in every village and in every place of worship. The government began to plan an equity-oriented national policy focused on people-centered development.

The results speak for themselves. Life expectancy has doubled since the mid-1990s. Premature mortality rates have fallen dramatically in recent years

In 1998 the government released a national development plan based on a comprehensive consultative process coupled with long-term visionary thinking called Vision 2020. The plan involves the principles of people-centered development and social cohesion. Central to the vision is health equity. The government understood that prosperity would not be possible without substantial investments in public health and health care delivery.

In the early 2000s, I visited President Kagame in Rwanda and observed over the course of the day the inclusive consultative process, which brought experts and stakeholders from around the country together to plan for the future. I was impressed, and remember thinking at the time that we in the US should be doing a lot more of this strategic sort of planning.

In 2003 the Rwandan constitution formalized the inalienable right to health. The Rwandan people made the commitment—in contrast to the violence which led to the 1994 genocide—to commit to, and invest in life.

Their work is bearing fruit.

Initially, PIH was a health care provider in the hospitals and health centers it started. But increasingly, PIH has transitioned into more of an advisory role. PIH now supports the Rwandan government in providing services to more than 865,000 people at three district hospitals and 41 health centers, with the help of 4,500 community health workers.

The Rwanda Human Resources for Health (HRH) Program was launched two years ago in collaboration with Harvard Medical School, USAID and other US government programs. About 70 to 100 clinicians, administrators, and planners from Harvard-affiliated hospitals work closely with the Rwandan Ministry of Health to develop the clinical service infrastructure and train healthcare providers.

These groups are laying groundwork that Rwanda is building on to establish its own mature health services. But that doesn’t mean the time for dreaming is over.

Paul Farmer’s next dream for Rwanda is to set up a major multidisciplinary research university in a rural area outside of Kigali. It’s part of his vision to move services, “out to where the people are.” It will train doctors, nurses, and community health workers; it will give broad practical instruction in the post-secondary space; it will give opportunity to people among the poorest regions of the country.

It’s a crazy idea, but—mark my words—you will see it alive in five years.

Farmer already has the Minister of Health and Rwanda’s President on board. He’s funded studies on long-term sustainability. He has initial planning money from two donors, and is working with Melinda Gates on development.

For having survived so much pain, Rwanda has proven itself extraordinarily resilient. Starting with PEPFAR’s HIV/AIDS relief and now the work being done by PIH Rwanda and others, investments in health truly are returning dividends in peace, growth, and healing.

It is global health diplomacy at its best.

Read more: http://themorningconsult.com/2014/06/watching-global-health-diplomacy-action-week-rwanda/