(The Washington Times, July 13, 2012)

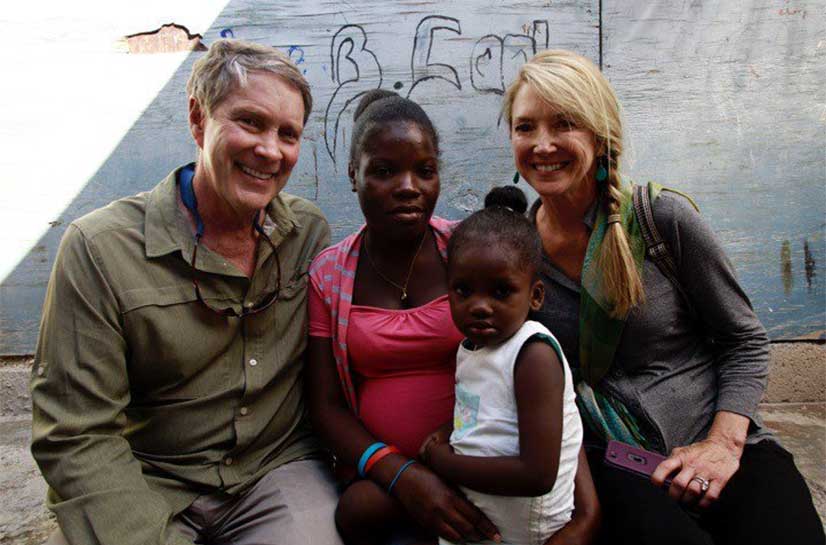

As a board member of the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund, I traveled to Haiti last month to check on the post-earthquake progress being made through the fund’s projects. What I saw confirms that developmental aid can have a greater impact than the humanitarian aid most people know.

Moments after the massive earthquake shook Haiti, more than 200,000 people died and nearly $8 billion worth of damage was done. Homes, businesses, schools and hospitals crumbled, all in a country already experiencing 70 percent unemployment. As a surgeon, I joined a volunteer medical response team from Samaritan’s Purse, and in the days following the quake, we helped care for hundreds of injured patients.

To lead the U.S. response, President Obama asked former Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush to raise money to help Haiti build its own sustainable path forward. The fund began making targeted investments, using a variety of tools to help Haiti “build back better.”

The problem with most disaster aid is that it’s temporary. For instance, flooding a developing country with free food and medicine can drive the small farmer or pharmacist out of business, further hurting the economy and leaving residents with less. Aid can be more effective if helpers buy food locally and work through local clinics to support, not undermine, local capacity.

This is why the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund embraced a new model that focuses on promoting economic growth and spurring job creation.

Economic growth generates lasting change, attracts investment, supports entrepreneurs and empowers citizens, providing them with tools to determine their own destiny. After billions of charitable dollars and donor aid are spent, the success — and sustainability — of Haitian reconstruction will depend on one key thing: a vibrant, inclusive private sector.

The fund recognized that economic growth calls for new development tools to facilitate access to capital. A simple grant can encourage dependency on free money — an untenable position in the long term. Alternatively, a program-related investment — a loan or equity investment — is a tool that brings about self-reliance and leads to sustainable growth. These tools come with contractual complexities and nonpayment risks, and the typical nongovernmental organization or development agency thus shies away. But the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund embraces this risk. In doing so, we are teaching a new pattern of development, catalyzing private support over public by a ratio of almost 4-1, and expanding the ability to use these funds. When these investments succeed, we reinvest the money for social and economic good. This is a cycle of smart investing.

In my visit to Haiti, I saw the power of these investment tools. One example is the Artisan Business Network (ABN), which the fund helped create with a combination of grants and loans to the artisan sector. The ABN connects more than 900 Haitian artisans, centralizing and guaranteeing product development, packaging, quality control and distribution to open doors to international markets.

When I visited the ABN hub in Port-au-Prince, I was picking out earrings for my two nieces alongside New York buyers selecting products for a bulk order. Already, the collaboration has seen large orders from retailers, including Macy’s and Anthropologie. Now other organizations are looking at the ABN as a scalable model. By combining grants and loans, we ultimately provided a hand up, not a handout, all while celebrating the culture and dignity of the Haitian people.

In addition, the fund makes equity investments, as we did for the Royal Oasis Hotel, which I visited. Under construction when the earthquake hit, the hotel faced a severe financing gap. The fund stepped in, providing equity that catalyzed contributions from other investors.

To date, Oasis has created more than 600 construction jobs and will sustain 300 permanent jobs. Equally important, its economic and human impact will ripple through the community, helping surrounding businesses, from shops on Oasis’ first floor to restaurants, airlines, tour guides and more. Indeed, it’s estimated that for every job created in the hotel, three indirect jobs will be supported in the surrounding community.

For the Oasis project, the fund did what the presidents wanted — it made a strategic investment, served as a catalyst and paved the way for others. The Oasis is more than a symbol of what it means to build back better — it will send the message that Haiti is truly open for business.

From health care to mobile media, we have started to think differently about how to achieve the best outcomes, improving the quality of life at home and abroad. It’s time we looked equally hard at aid and development, challenging the old ways of doing business, experimenting with new tools and models, and aiming to create self-sustaining economies and entrepreneurs. In that regard, a good place to look for such innovative development is the investments made by the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund.

William H. Frist is a former heart and lung transplant surgeon and served as the U.S. Senate majority leader from 2003 to 2007.

This article was originally featured in The Washington Times http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2012/jul/13/helping-haiti-build-back-better/