(The Week, Posted on June 19, 2012)

By Bill Frist, M.D.

The most impressive part of any hospital or health clinic is the caring, skilled employees who prevent and treat illness. But the workforce we have is not enough.

As I visit health programs in far off corners of the world and right here at home, the most impressive part of any hospital or clinic is the health workers themselves — the hands behind the health care that is provided to mothers and newborns, to children and the elderly, to teens and adults to prevent and treat illness.

Health workers heal. It’s as simple as that. And in this country, and around the world, there are not enough of them. Doctors are included in that shortage, but it doesn’t stop there. Recent estimates suggest the world is short some 4 million to 5 million community health workers, midwives, pharmacists, lab technicians, nurses, and doctors. Fifty-seven countries have severe health workforce shortages — meaning there are less than 23 clinicians per 10,000 people.

And health workers, particularly in developing countries, are scarcest in the poorest communities and neighborhoods — both rural and urban — where poverty, poor sanitation, and disease conspire to take the lives of children and adults through preventable killers like pneumonia, diarrhea, pregnancy complications, and tuberculosis.

Fifty-seven countries have severe health workforce shortages.

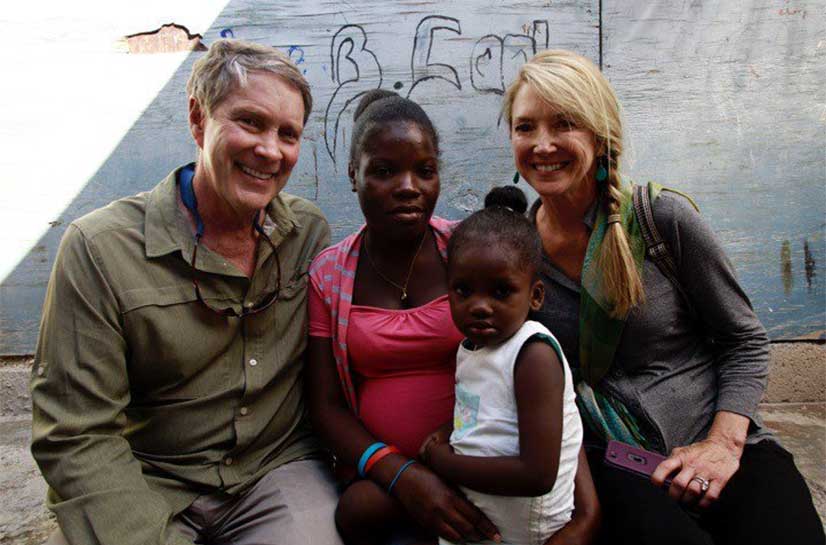

Later this week I am heading back to Haiti with the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund to review past investments in sustainable human health capital. Haiti is in dire need of indigenous health workers who are from and remain committed to their local communities. Long-term health and economic results can only be achieved by partnering with Haitians to build health training and service programs that they own and that they populate.

In targeted areas around the world, training armies of much-needed health workers has become a smart, key goal of U.S. foreign assistance. We are helping train new midwives, community health workers, lab technicians, and nurses through partnering programs supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These new health workers are serving in communities hardest hit by infectious diseases and the complications from pregnancy and childbirth.

And it works! Countries that have made a concerted effort to increase the numbers and skills of their health workforces have shown tremendous progress: Malawi has trained more than 10,000 health surveillance assistants in the past 20 years, and in the same period child mortality dropped almost 60 percent. In India, turning normal community members into lay health workers to support healthier newborn care practices reduced newborn deaths by over 50 percent.

Training community-level health workers does not have to be expensive — people who can provide the most basic levels of treatment for sick children and promote healthy practices can be trained for as little as $300. More-skilled community health workers and midwives cost roughly 10 times that amount to train. These workers provide the lifesaving interventions needed to address most of the leading causes of death of newborns and children — all with no need for huge medical school bills. It’s basic health care, but it is lifesaving.

Highlighting the humble service of health workers around the world is the subject of a campaign launched by Save the Children, with whom I have traveled to countries like Bangladesh and Mozambique to witness these health workers going about their daily tasks. The care is effective and affordable. In fact, I think we in the U.S. have a lot to learn from these community health workers delivering local care. Take a look at some of the powerful stories at www.goodgoes.org, where you glimpse the simple and affordable care provided by people who go the extra mile on behalf of others.

No matter what diseases and conditions are threatening, and what new technologies for treatment might come along, we can say for sure that progress will depend on an expanded army of health workers, properly trained and placed, with the right skills and supplies, intent on delivering the best quality health care possible.

As we look at America’s international assistance around the world, surely one of the best examples of success can be seen in the faces of these committed community servants.

This article was originally featured in The Week http://theweek.com/article/index/229433/the-world-needs-more-health-care-workers-mdash-millions-more