(The Huffington Post, October 2, 2013)

By Sen. Chris Dodd and Sen. Bill Frist, M.D.

When we served together in the Senate, we found ourselves on different sides of a variety of issues. But when it came to common-sense measures that benefitted our country and our citizens, we pulled together.

We were proud to cosponsor the Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act because we knew its reforms would help save thousands of lives in America. Today, we’re pulling together to support another common sense measure — early education for all children in America.

There is little debate that education is key to a child’s future success, or that it is key to our global competitiveness as a nation. But one of the most overlooked ways to improving educational opportunities in America is reaching kids early enough.

Two out five children in America have had no preschool or kindergarten education by age 5. When these children do enter school, many are already behind their peers.

As science has clearly shown in recent years, most brain development is complete well before a child enters kindergarten. Without early learning opportunities, many children are entering school without the tools they need to stay on track and succeed.

Unfortunately, poor children in America are most likely to lose these critical opportunities. As a result, children from low-income families can easily fall 18 months developmentally behind children from middle-class families by the time they’re just 4 years old.

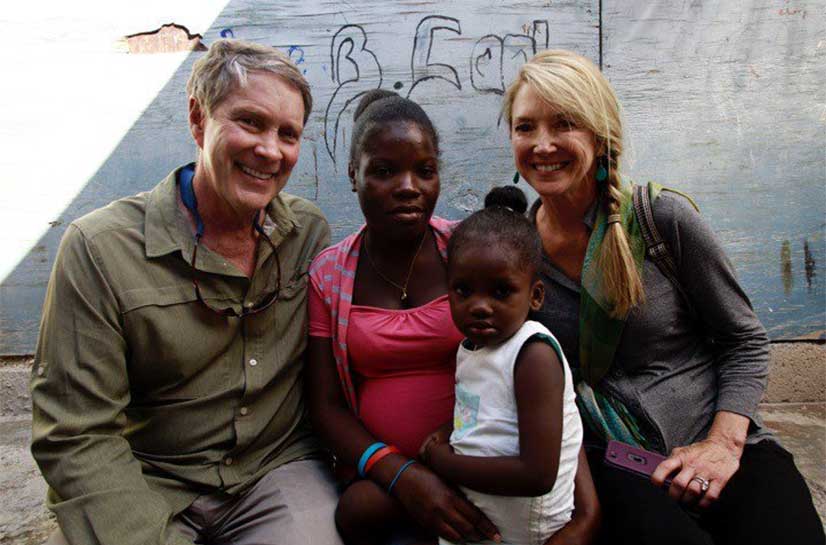

Let us share one anecdote from our friends at Save the Children, to show just what a difference early learning can make. The non-profit organization recently received a letter from the superintendent of an isolated, rural school district in Alpaugh, California.

Poverty, language and cultural barriers, and lack of parental engagement in the education system have long meant that children in the district enter school ill-prepared to succeed, he said.

But this year, he reported, the first group of children who had been through Save the Children’s early learning program entered the first grade. Every one of them is reading at grade level, he said, “something unheard of in past classes.”

This success is particularly significant because research is clear about the importance of reading at grade level by the time a student enters the 3rd grade.

Helping all families have access to children’s books and information on how they can support their child’s development goes a very long way. And giving more children the chance to attend high-quality preschool is the smart thing to do.

One study found that every public dollar spent on preschool returns $7 through increased productivity and savings on government assistance programs and criminal justice costs.

We all have a role to play in helping more children succeed. That can be through volunteering in our own communities, contributing to programs that make a difference, or voicing support for proposals to expand high-quality early education in America.

There is critical work taking place in our country to improve K-12 public education. However, there is more to do to ensure millions of children do not fall behind before they even reach school. Common sense tells us, investing in our children early is the right thing to do.

This blog post is part of a series produced by The Huffington Post and Save the Children, as part of the latter’s drive for universal early education, which is the focus of their gala on October 1 in New York. For more information about Save the Children, click here.

This article was originally featured in The Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.com/chris-dodd/its-common-sense-to-come-_b_4031431.html